Coagulation and COVID-19 – Part 1

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has caused immense human and economic suffering. It has also inspired some remarkable scientific and medical achievements. We have seen the development and rollout of an effective vaccine in record time, and the RECOVERY trial, with its adaptive design and simplified procedures, is an innovative approach to rapid yet rigorous testing of potential COVID-19 treatments.

There is still much to learn about the virus and the disease it causes. Patients with the virus often present with coagulopathy, sometimes as deep-vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (DVT or PE, respectively), and sometimes in the form of cardiac microthrombi, tiny clots that can damage the heart and cause myocardial infarction (MI). The composition of these microthrombi is different from clots found in the hearts of MI patients who were not infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Coagulopathies are potentially preventable and treatable with anticoagulants. The REMAP-CAP study found that starting anticoagulation with subcutaneous heparin or enoxaparin, at prophylactic doses, early in the course of disease of hospitalized patients decreased the risk of death after 30 days compared with no anticoagulation.

The problem with anticoagulants is that they – not unexpectedly – increase the risk of bleeding. And questions remain around the utility of therapeutic (higher) doses of anticoagulation, whether extended anticoagulation after hospital discharge is needed, and if the newer, oral anticoagulants might be beneficial. See the summary in the BMJ written by Professor Beverly Hunt of Guy’s & St Thomas’ in London and colleagues for more about these issues.

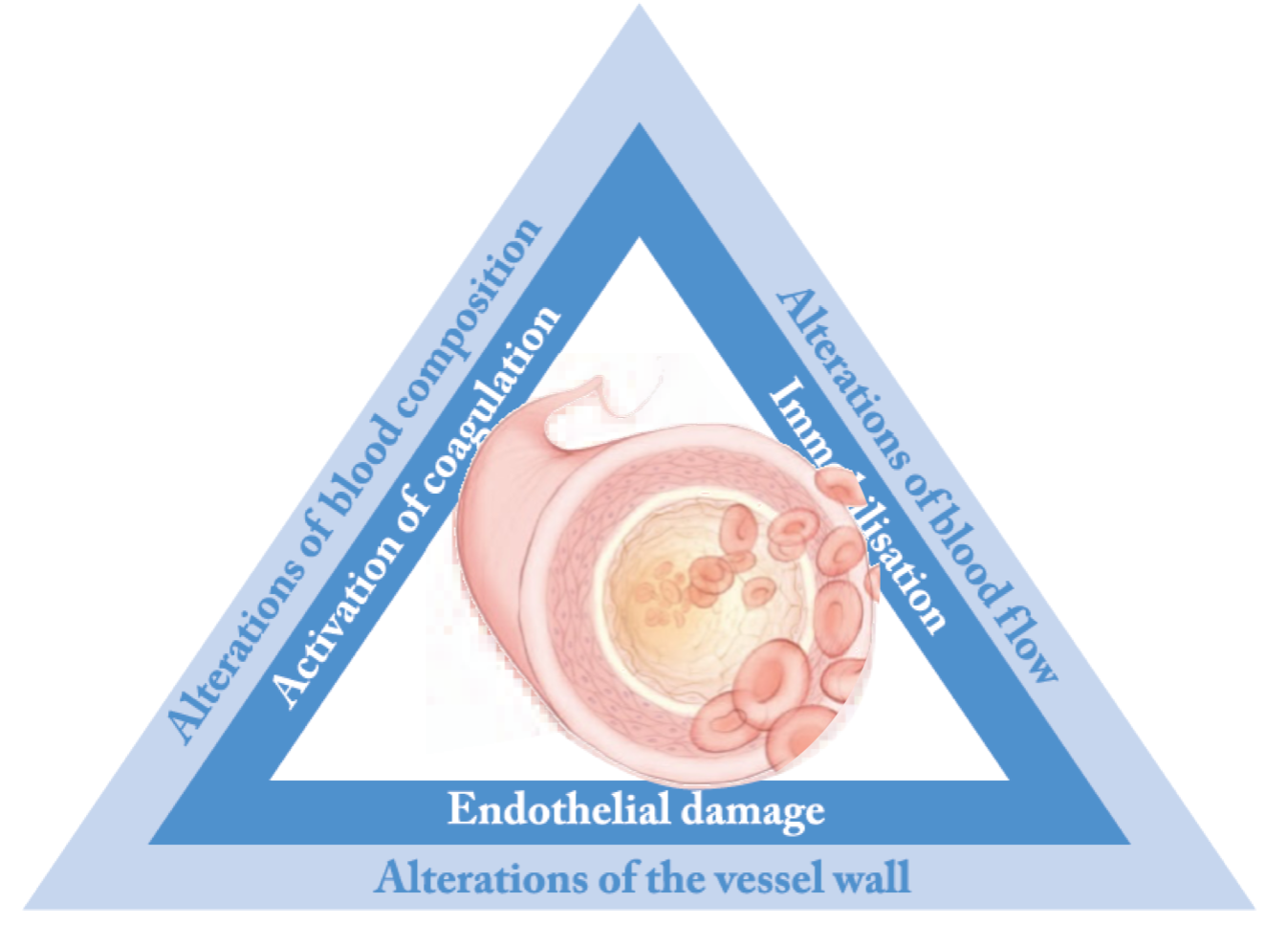

Thrombosis – the inappropriate clotting of blood in the body – is itself a major cause of illness and death worldwide, causing about a quarter of global mortality. Thrombotic conditions include DVT, PE, ischaemic stroke and MI, and have been known since antiquity. Huang Ti apparently describes DVT or peripheral artery disease in about 260 BC, and it has been proposed that Psalm 137 is referring to the symptoms of a stroke of the left middle cerebral artery.

Treatments for thrombotic conditions have been recognized for almost as long, even if neither the mechanism of disease nor the mode of action of the treatment were understood at the time; medicinal leeches were used in Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3500 years ago. But it was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that Rudolf Virchow coined the terms ’thrombosis’ and ‘embolus’ and described the ‘fibre theory’ of coagulation. It is his famous triad that still informs much of our thinking today.

After medicinal leeches, the first effective antithrombotic was heparin, discovered almost by accident and isolated in the early twentieth century. Another effective anticoagulant, warfarin, was developed as a rat poison and only used therapeutically in humans after an American soldier tried (and failed) to commit suicide using it.

Because clots are made from platelets as well as fibrin, antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin and the class of molecules known as P2Y12 inhibitors can be effective in certain indications, and are used widely to treat MI. Antiplatelets are also being evaluated in the REMAP-CAP study.

While effective, heparin and warfarin are problematic therapies. Heparin is manufactured from pigs, primarily in China, and is chemically ill-defined, consisting of a mix of differing lengths of sulphated sugar molecules. It acts indirectly on components of the coagulation cascade. Fractionated low-molecular weight heparins, such as enoxaparin, are more defined but still require subcutaneous delivery.

Warfarin is taken orally, and is effective not just against venous thrombosis but also against ischaemic stroke caused by atrial fibrillation. However, it too acts on multiple components and its dose must be carefully adjusted, its absorption is very sensitive to diet, and it has multiple drug-drug interactions. Failure to tailor the dose accurately and persistently can cause major bleeding (especially haemorrhagic stroke) on the one hand, or thrombotic events on the other.

These shortcomings led to the rational development of a family of orally available anticoagulants, targeted against key effectors in the coagulation cascade. Direct-acting oral anticoagulants, or DOACs, have been marketed in various indications since 2008, and are effective against venous and arterial thrombosis. Like any anticoagulant they increase the risk of bleeding, but are associated with less critical and fatal bleeding than warfarin.

DOACs are being evaluated for patients with COVID-19 (see for example here and here at clinicaltrials.gov), and the results of these studies are eagerly expected. But is there a solution to the bleeding problem, and what does the future look like for treatment and prevention of thrombotic disease more generally? These are questions I’d like to explore in my next post.

Stay tuned!

AS&K's medical content team has a wealth of experience in developing communications for healthcare professionals when clarity of the science and clinical data is needed most.

Contact our team at sales@asandk.com for a consultation today.